ESA Publications News

Volume

85, Number 2, April 2004

Volume

85, Number 2, April 2004

Cover

Photo: Seastars (Pisaster ochraceus) foraging on mussels and barnacles in the

low intertidal region at Strawberry Hill, Oregon, a wave-exposed habitat. Prey

(mussels) recruitment and growth were higher at exposed than at sheltered locations,

and higher at Strawberry Hill than at Boiler Bay, 80 km north. Field experiments

indicated the resulting annual pulses of abundant food, visible as a black zone

of mussels (Mytilus trossulus) between the seastars and the permanent M. californianus

zone (top), attract seastars, leading to higher predation intensity than observed

at the other sites. Prey production may therefore underlie variation in the

strength of keystone predation. These or similar sites will be the focus of

an overnight preconference field trip during the 2004 ESA meeting, when tides

will be very low. Photo by Bruce Menge, Department of Zoology, Oregon State

University, Corvallis OR 97331

Table of Contents

(click on a title to view that section)

Governing

Board

ANNOUNCEMENTS

Society Notices

New ESA Officers and Board Members 2004

Request for Student Awards Judges

International Collaborations: Robert H. Whittaker Fellowship

Desert Ecology: Forrest Shreve Student Research Award

Society

Section and Chapter News

Applied

Ecology Section Newsletter

Southeastern Chapter Newsletter

Other

Notices

Manual on Coastal Habitat Monitoring

Resolution of Respect: Frank A. Pitelka

SOCIETY

ACTIONS

Highlights of the 21–22 November Governing Board Meeting

Minutes of the 21–22 November Governing Board Meeting

DEPARTMENTS

Ecology 101

Ecology Teaching Tips for First-year Professors. K. Wilson

and S. E. Hampton

MEETINGS

Meeting Calendar

ESA Annual Meeting, 1–6 August 2004, Portland, Oregon

2004 North American Forest Biology Workshop: Houghton, Michigan

2004 International Symposium on Plant Responses to Air Pollution

and Global Changes:

Tsukuba, Japan

Second Biennial Conference of the International Biogeography

Society: Shepherdstown, West Virginia

CONTRIBUTIONS

Commentary

Scientific Writing and Publishing—a Guide for Students.

C. D. G. Harley, M. A. Hixon, and L. L. Levin

An Ecological Purpose for Life: Responsibility to Earth. J.

S. Rowe

Things That Can Go Wrong With PowerPoint Presentations. M.

Köchy

Deviations and Errors: Standards in Statistics. A. G. Hart

The BULLETIN OF THE ECOLOGICAL

SOCIETY OF AMERICA (ISSN 0012-9623)

is published quarterly by the

Ecological Society of America, 1707 H Street, NW, Suite 400, Washington, DC

20006.

It is available online only, free of charge, at <http://www.esapubs.org/bulletin/current/current.htm>.

Issues published prior to January 2004 are available through

<http://www.esapubs.org/esapubs/journals/bulletin_main.htm>

Bulletin

of the Ecological Society of America, 1707 H Street, NW, Washington DC 20006

(541) 754-4772, Fax: (541) 754-4799,

E-mail: [email protected]

| Associate

Editor David A. Gooding ESA Publications Office, 127 W. State Street, Suite 301, Ithaca, NY 14850-5427 E-mail: [email protected] Production Editor Regina Przygocki ESA Publications Office, 127 W. State Street, Suite 301, Ithaca, NY 14850-5427 E-mail: [email protected] |

Section

Editor, Technological Tools D. W. Inouye Department of Zoology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 E-mail: [email protected] Section Editor, Ecology 101 H. Ornes College of Sciences, SB310A, Southern Utah University Cedar City, UT 84720 E-mail: [email protected] Section Editor, Public Affairs Perspective N. Lymn Director for Public Affairs, ESA Headquarters, 1707 H Street, NW, Suite 400, Washington, DC 20036 E-mail: [email protected] |

| Regular member: | Income level | Dues |

| <$40,000 | $50.00 | |

| $40,000—60,000 | $75.00 | |

| >$60,000 | $95.00 | |

|

Student member:

|

$25.00 | |

| Emeritus member: | Free | |

|

Life

member:

|

Contact Member and Subscriber Services (see below) |

ANNOUNCEMENTS

ANNOUNCEMENTSESA 2004 Election Results

The winners of the 2004 elections are:

President-elect (2004–2005), President (2005–2006), Past President (2006–2007)

Nancy Grimm

Department of Biology

Arizona State University

Vice President for Science (2004–2007)

Gus Shaver

The Ecosystems Center, Marine Biological Laboratory,

Wood’s Hole, Massachusetts

Secretary (2004–2007)

David Inouye

Department of Biology

University of Maryland

Member-at-Large (2-year term, 2004–2006)

Dee Boersma

Department of Zoology

University of Washington

Shahid Naeem

Department of Biology

Columbia University

Board of Professional Certification (3-year term, January 2004–December 2006)

Jeff Klopatek

School of Life Sciences

Arizona State University

David Breshears

Environmental Dynamics and Spatial Analysis Group

Los Alamos National Laboratory

Diane Wickland

Terrestrial Ecology Program

NASA Headquarters

REQUEST FOR STUDENT AWARD JUDGES

Murray

F. Buell Award

E. Lucy Braun Award

Judges are needed to evaluate candidates for the Murray F. Buell Award for the outstanding oral presentation by a student and the E. Lucy Braun Award for the outstanding poster presentation by a student at the Annual ESA Meeting at Portland, Oregon in 2004. We need to provide each candidate with at least four judges competent in the specific subject of the presentation. Each judge is asked to evaluate 3–5 papers and/or posters. Current graduate students are not eligible to judge. This is a great way to become involved in an important ESA activity. We desperately need your help!

Please complete and send this form by mail, fax, or e-mail to the Chair of the Student Awards Subcommittee: Christopher F. Sacchi, Department of Biology, Kutztown University, Kutztown, PA 19530 USA. Call (610) 683-4314; FAX: (610) 683-4854 or e-mail: [email protected]

If you have judged in the past several years, this information is on file. If you do not have to update your information, simply send me an e-mail message, “Yes, I can judge this year.”

Name

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Current mailing address _______________________________________________________________________________

June/July mailing address _____________________________________________________________________________

Current telephone Summer telephone ____________________________________________________________________

E-mail Fax __________________________________________________________________________________________

Year M.S. received Year Ph.D received ______________________________________

Areas

of expertise (check all that apply):

— Discipline Research approach (please rank) Organisms

— Botany Population ecology Vertebrates

— Zoology Community ecology Types:

— Microbiology Ecosystem ecology Invertebrates

— Applied ecology Types:

— Habitat Physiological ecology Plants

— Soil Behavioral ecology Types:

— Terrestrial Paleoecology Fungi

— Freshwater Theoretical ecology Microbes

— Marine Evolutionary ecology Types:

Provide

a few key words or phrases that describe your interests and expertise: _________________________

________________________________________________________________________

Back

to Table of Contents

International Collaborations: Robert H. Whittaker Fellowship

One to two awards annually of $750–1500 are available to promote active collaboration and exchange of ideas between foreign and U.S. ecologists. Awards are given to foreign scientists to help defray the cost of travel to the United States for research collaboration with colleagues. Requirements: the foreign ecologist must possess an earned doctorate, reside in a foreign country, and not be a U.S. citizen. Application for the fellowship may be made directly by the foreign ecologist or by a U.S. scientist on behalf of a foreign scientist. Either the foreign scientist or the U.S. ecologist must belong to the ESA. Applicants should submit a proposal describing the purpose of the travel, the nature of the research, travel itinerary, and costs. Proposals should not exceed four double-spaced pages for these materials. The foreign ecologist’s CV and a one-page letter of support from the United States collaborator should be appended; these items are not included in the page limit.

Desert Ecology: Forrest Shreve

Student Research Award

One to two awards annually of $1000–2000 are available

to support research in the hot deserts of North America: Sonora, Mohave, Chihuahua,

and Vizcaino. Projects should be clearly ecological and should increase our

understanding of the patterns and processes of deserts and/or desert organisms.

Proposals should not exceed 5 double-spaced pages for all material and should

include objectives, importance, background, methods, literature cited, and

justified budget. Proposals will be ranked based on the importance of the

project to understanding desert ecology, feasibility, experimental design,

and innovation.

The postmark deadline for both the Whittaker and Shreve Awards is 30 April

2004. Send six printed copies of the proposal to:

Wendy B. Anderson

Department of Biology

Drury University

900 N. Benton

Springfield, MO 65802

(417) 873-7445

E-mail: [email protected]

Applied Ecology Section Newsletter

Call

for Nominations for Section officers for 2004–2006

The Applied Ecology Section is seeking candidates for the offices of Chair,

Vice-Chair, and Secretary. Applied Ecology Section Officers serve a 2-year

term. Final nominees will be selected by the Nominating Committee by 15 June,

and the election will be held by e-mail in July. Responsibilities of the Officers

are described in the Section Bylaws, which are reprinted below.

Article 5. OFFICERS. The officers of the Section shall be a Chair, Vice-Chair,

and Secretary. The Officers shall comprise the Section Executive Committee

and may act on behalf of the Section during intervals between annual meetings.

Voting for Officers shall be by either mail or by email ballot distributed

to members in odd numbered years. Officers shall serve for a term of two years

and not be eligible for re-election. The Chair and Secretary assume office

in the year the election is held, and the Vice-Chair assumes office the following

year.

Article 6. CHAIR. The Chair shall preside at the business meetings of the

Section, authorize expenditures of Section funds, and shall promote in every

practical way the interests of the Section. The Chair shall appoint a Nominating

Committee, which shall prepare a slate of candidates for each office.

Article 7. VICE-CHAIR. The Vice-Chair shall be responsible for arranging the

scientific program for all meetings of the Section, and shall assume the duties

of the chair whenever that person is unable to act.

Article 8. SECRETARY. The Secretary shall keep the records of the Section

and an up-to-date membership and mailing list, and shall perform such other

duties as may be assigned by the Chair.

Duties that may be assigned by the Chair can include: submits information

to ESA Bulletin by deadline for publication in the next ESA Bulletin; takes

minutes at the annual meetings; maintains and updates the web page; assists

the Chair and Vice Chair with distributing information and other tasks as

deemed by the Chair; assists with organizing and tallying votes for the Student

Travel Award; counts ballots for elections.

Please send nominations, including a one-paragraph biosketch that describes

your vision as an Officer of the Applied Ecology Section, by 15 May 2004 to

the Applied Section Chair:

Paulette Ford, Research Ecologist

Rocky Mountain Research Station

333 Broadway SE, Suite 115

Albuquerque, NM 87102-3497 USA

(505) 766-1044

Fax: (505) 766-1046

E-mail: [email protected]

SOUTHEASTERN

CHAPTER NEWSLETTER

Issue 2004–1

Chapter Officers

Chair: Paul Schmalzer (2002-2004) [email protected]

Vice-Chair: Joan Walker (2003-2005) [email protected]

Secretary/Treasurer: Yetta Jager (2002-2004) [email protected]

Web-Master: Mark Mackenzie [email protected]

Chapter home page: ‹http://www.auburn.edu/seesa/›

Spring 2004 Chapter Meeting in Memphis

Please attend our business meeting and luncheon on Friday, 16 April at noon (FEC room 217) at the meeting of the Association of Southeastern Biologists (ASB) in Memphis, Tennessee. This will be our opportunity to vote on the poster award and to elect the chair and secretary/treasurer for the term beginning August 2004. Scott Franklin, an ESA-SE member from the University of Memphis, will be one of our hosts. Dan Simberloff will give the ASB keynote address the evening of Wednesday, 14 April, and a social will be held at the Gibson guitar factory on 15 April. The ESA Southeastern Chapter will co-host with the TN Exotic Pest Plant Council a symposium, “Invasive Plant Awareness and Research: Priority Status.” The symposium, coordinated by Pat Parr and Jack Ranney, will be held Thursday morning, 15 April. Visit ‹http://www.people.memphis.edu/~biology/asb/›

Membership Renewal and Odum Award

Please remember to renew your membership in the SE chapter when you renew your ESA membership. Your donations to the Eugene P. Odum Fund support the 2004 Best Student Paper Award. We are within $1250 of our goal of $10,000, which is the amount needed to make the Odum Fund sustainable.

A proposed bylaws amendment to establish the QUARTERMAN-KEEVER poster award for the best student poster was published in the January 2004 ESA Bulletin. The amendment will be voted on at our April 2004 meeting.

Southern Appalachian Man and the Biosphere Cooperative and Foundation

SAMAB has the goal of “promoting environmental health, stewardship, and sustainable development of natural, economic, and cultural resources in the Southern Appalachians.” Learn more at ‹http://samab.org›. SE Chapter members may also be interested in data available at the Southern Appalachian Information Node, National Biological Information Infrastructure, see ‹http://sain.nbii.gov›

Farm Bill Funding for Conservation

The USDA Continuous Conservation Reserve Program is available to assist private landowners with water and land conservation. CP-22-Riparian Forest Buffers offers significant incentives to farmers to restore trees to riparian areas to benefit stream banks and improve water quality in streams. For more information, see ‹http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/›

Upcoming Meetings and Symposia

ESA 2004 Meeting

The ESA Annual Meeting will be in Portland, Oregon, on 1–6 August. The Chapter will have a brown bag lunch meeting on Tuesday, 3 August. Check the program for time and place. We will discuss symposium ideas or other Chapter-sponsored activities for the 2005 ASB and ESA meetings.

ASB 2005 Meeting

ASB will meet on 13–16 April 2005 in northern Alabama. Proposals for symposia at this meeting will be due in early September 2004.

ESA 2005 Meeting

In 2005, ESA will meet with INTECOL in Montreal, Canada on 7–12 August. Proposals for symposia at this meeting will also be due in early September 2004.

SEAFWA 2004

The South Carolina Department of Natural Resources invites you to the 58th Annual Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies Conference, Hilton Head, South Carolina, 30 October–3 November 2004 ‹www.scdnr.state.sc.us/seafwa›

Keeping in Touch

Check the Chapter home page ‹http://www.auburn.edu/seesa/› for updates and additional information. Join the Southeastern Chapter of ESA LISTSERVER. To join the ListServer, send a message to [email protected] with “subscribe scesa” in the body of the message. Please send news or announcements to [email protected] for distribution to the listserv, or to [email protected] for inclusion in the next quarterly newsletter.

Respectfully,

Yetta Jager

Newsletter Editor

Coastal resource managers, practitioners, and the public

now have a consolidated set of science-based tools available for planning

and conducting monitoring associated with restoration projects in habitats

throughout U.S. coastal waters.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers

for Coastal Ocean Science have brought together for the first time key restoration

monitoring information applicable to coastal habitats nationwide. Prepared

under the Estuary Restoration Act of 2000, the new document, “Science-Based

Restoration Monitoring of Coastal Habitats, Volume One: A Framework for

Monitoring Plans Under the Estuaries and Clean Waters Act of 2000 (Public

Law 160-457)” offers technical assistance, outlines steps, and provides

useful tools for developing and carrying out monitoring of coastal restoration

efforts. While designed to support the monitoring of projects funded under

the Estuary Restoration Act, the framework and tools presented in this document

have broad applicability.

“Given the broad diversity and geographic scope of our nation’s

coasts, there clearly is no one-size-fits-all, cookie-cutter approach to

science-based restoration monitoring,” said lead author Gordon Thayer,

of NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science/Center for Fisheries

and Habitat Research, in Beaufort, North Carolina. “Individual coastal

managers, working with their public and private-sector partners, can use

this document to determine the individual strategies best suited to a specific

restoration effort or region.” Thayer emphasized that the newly released

NOAA report includes consistent principles and approaches likely to be applicable

to a wide range of coastal restoration efforts, including those undertaken

without federal funding support.

Along with providing a framework for structuring monitoring efforts, the

newly available manual provides an introduction to restoration monitoring

related to specific coastal habitats: water column, rock bottom, coral reefs,

oyster reefs, soft bottom, kelp and other macroalgae, rocky shoreline, soft

shoreline, submerged aquatic vegetation, marshes, mangrove swamps, deepwater

swamps, and riverine forests.

A companion volume, “Science-Based Restoration Monitoring of Coastal

Habitats, Volume Two: Tools for Monitoring Coastal Habitats,” is due

for release later this calendar year. This document will delve deeper into

monitoring approaches for the selected coastal habitats, providing techniques

for monitoring them. Additionally, volume two provides tools such as a searchable

database of restoration monitoring programs nationwide, a guide to selecting

reference sites, and a discussion of the monitoring of social and economic

aspects of coastal restoration.

The NOAA report is expected to be useful to scientists, managers, and citizens

involved in planning and conducting restoration monitoring efforts, including

individuals in academia, industry, government interests at all levels, nongovernmental

organizations, and the media. Copies of the report, Science-Based Restoration

Monitoring of Coastal Habitats, Volume One: A Framework for Monitoring Plans

Under the Estuaries and Clean Waters Act of 2000 (Public Law 160-457) can

be downloaded as a PDF file by visiting ‹http://coastalscience.noaa.gov/ecosystems/estuaries/restoration_monitoring.html›

Additional information and printed copies of the report are also available

by contacting: ‹[email protected]› or:

Teresa A. McTigue, Ph.D

National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science (N/SCI)

1305 East-West Highway, Room 8128

Silver Spring, MD 20910

(301) 713-3020 x 186

Fax: (301) 713-4353

Frank A.

Pitelka

1916–2003

Frank Alois Pitelka, Professor Emeritus of Zoology at the University of

California at Berkeley, died on 10 October 2003 at his daughter’s home

in Altadena, California. His death, at age 87, was caused by complications

from prostate cancer. Frank was a prominent player in the early discussions

of concepts that underpin much of modern ecology. The scope of empirical

studies conducted by Frank and his students was enormous and addressed such

diverse topics as speciation, population regulation, bioenergetic constraints,

territoriality, the niche concept, Arctic ecology, and the evolution of

breeding systems. Frank was also a demanding, but supportive, mentor to

the 37 Ph.Ds and 8 postdocs whom he trained at Berkeley.

Frank was born on 27 March 1916 and raised in Berwyn near Chicago. Both of his parents were born in Czechoslovakia, although they first met in Chicago. As a result, Frank learned to speak Czech at home and continued to do so at every opportunity throughout his life. Frank’s father was a building contractor, and at his insistence, Frank studied the business curriculum at Morton High School and Junior College in Cicero, a neighboring suburb of Chicago. (Frank’s business training was reflected in the amazing speed of his typing and shorthand. His letters were swiftly drafted and, as a consequence, they retained the vividness of the original observations that prompted him to write.) In 1936, following his graduation from Junior College, Frank took a position as the secretary to one of the managers of the Electromotive Corporation, a subsidiary of General Electric. During this time, Frank studied on his own and passed the courses required for admission to the University of Illinois, where he majored in Chemistry and Zoology and graduated summa cum laude in 1939.

Frank started on the naturalist’s path at an early age. In sixth grade one of his teachers, Miss Luckness, took the class on bird walks. He was so taken by this experience that he started watching birds on his own. In 1933, as his interests in the natural history of birds broadened, Frank learned of the Prairie Club (a Midwestern version of the Sierra Club). He asked his teachers how he might attend club meetings. They arranged a meeting with Mrs. Nellie J. Baroody, a cultured woman who was active in circles devoted to natural history and conservation. She took a strong interest in Frank and invited him to participate in family activities. He accompanied her to public lectures and concerts as well as on field trips to prairies and the Lake Michigan dunes. It was through Mrs. Baroody that Frank was introduced to biologists at the Field Museum and the University of Chicago. Frank was always deeply grateful for Mrs. Baroody’s sponsorship; she opened up a whole new world beyond his ethnic neighborhood, and introduced him to the music and cultivated lifestyle that he enjoyed throughout his life. Frank honored Mrs. Baroody by donating a student award in her name to the American Ornithologists’ Union.

Frank started to develop his editorial skills at an early age by assisting Rudyard Boulton at the Field Museum with Bird Lore. He began publishing his observations on birds in 1935. He entered the University of Illinois in 1937, even though General Electric made him attractive offers to remain with the company. He was somewhat older, with more developed interests than the average undergraduate, and the ecologists on the faculty, S. Charles Kendeigh and Victor E. Shelford, treated him like a graduate student. He shared an office with two other noteworthy students of Kendeigh, Eugene Odum and Frank Bellrose. Frank had access to Kendeigh’s library and read extensively on his own. He had a vivid memory of running across Charles Elton’s 1927 book on animal ecology. He put everything aside and read into the night until he had finished. Elton had a profound influence on Frank’s thinking—an influence that Frank put into context in 1957 and 1958 when he had an NSF senior fellowship to work with Elton’s group at Oxford University.

Kendeigh and Shelford, who both received the Eminent Ecologist award, stimulated new interests in Frank and broadened his perspective. Shelford spent much of the 1920s and 1930s documenting the composition of North American biotic communities, including soft-bottom marine invertebrates, and with Frederic E. Clements, developed the biome concept. Kendeigh, who hired Frank as his research assistant, emphasized studies of the distribution and abundance of birds, and had students in his ecology class draw maps of the distributions of biomes. No doubt as a result of these influences, some of Frank’s early work included a review of the distribution of birds in relation to major biotic communities, including a map of North American biomes cited in textbooks, and the mapping of soft-bottom invertebrate communities in Tamales Bay, California. The biome map was Frank’s senior thesis and brought an earlier map, by Shantz and Zon, up to date. Frank’s map differed from the others in acknowledging that there are extensive regions that are best treated as “ecotones.”

Frank moved to Berkeley, California, in 1940 with the intention of working on a Ph.D under Joseph Grinnell’s direction. Grinnell died suddenly, however, of a heart attack just before Frank arrived. There followed an interlude during which Frank worked on a variety of topics, including studies on the rocky intertidal communities at Friday Harbor, Washington. Unfortunately, this work was never published.

It was at Berkeley that his romance with a fellow graduate student, Dorothy Riggs, blossomed and eventually led to a happy marriage with three children. Dorothy became a noted electron microscopist and held a research position in the Cancer Research Genetics Laboratory and an appointment as Adjunct Professor of Zoology until her retirement in 1984. She died 10 years later, but two sons, Louis and Vince, and a daughter, Kazi, have survived their parents, as have five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

As a student of Alden Miller, Frank was based in the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology where the Grinnellian tradition remained strong. During the 1940s and 1950s much emphasis at the Museum was focused on building collections for the study of geographic variation. Frank’s doctoral research, for which he was awarded a Ph.D in 1946, took the form of a careful analysis of what can, and cannot, be learned from such data. In two monographs, one on shorebirds (dowitchers in the genus Limnodromus) and the other on the American jays (Aphelocoma), Frank developed hypotheses about how speciation may have proceeded within each of these two groups of closely related species. These monographs set new standards, broadened the conceptual scope of museum-based studies, and continue to figure importantly in the analyses of biogeographic patterns, largely because of the extensive and carefully gathered data that they contain.

Frank also was an important pioneer in behavioral ecology. By producing superb papers that served as exemplars, he played an important role in defining the major questions and lines of approach in this discipline. Starting with his early work on territoriality and courtship in hummingbirds, he consistently placed behavior in an ecological context long before this was fashionable. Frank’s extensive research on shorebirds (on both their breeding and wintering grounds) laid the groundwork for comparative analysis of behavior. This work was rich in details about foraging behavior, predator avoidance, interspecific interactions, and the timing of activities in a highly variable environment. In the late 1970s Frank started to collaborate with some of his graduate students on a long-term study of the Acorn Woodpecker at the Hastings Reservation in the Carmel Valley of California. This investigation, which continues, has yielded some of our earliest and most convincing demonstrations of cooperative breeding and kin selection.

In addition to his impact on avian ecology and ornithology in general, Frank made major contributions in other areas. Indeed, in some circles he is best known for his work on the interactions of small mammals with their food supply and predators. In the 1950s, in collaboration with Arnold Schultz, a plant ecologist and colleague at Berkeley, he developed the nutrient recovery hypothesis to explain population cycles of brown lemmings in the arctic tundra near Barrow, Alaska. Although subsequent work has not supported the details of this well-known hypothesis, particularly its emphasis on changes in quality of forage, it did inspire later research that documented the impact of small mammals on tundra and grassland vegetation. Furthermore, the interaction of lemmings with the quantity of available forage remains a favored explanation for lemming cycles. The studies by Frank and his students on the territorial and breeding responses of avian predators to fluctuations in lemming densities are still regularly cited. Concurrent studies in the Arctic included those of breeding populations of shorebirds, which began in the 1950s and blossomed in the 1970s, and studies of the demography of longspurs. Frank was clearly in his element during these 25 years of active field work in the Arctic, as anyone who had the good fortune to hear his enthusiastic daily reports of the latest discoveries can testify.

Because of his interest in population dynamics, Frank was an ardent participant in the debates that sprang up after 1954 about the regulation of populations. Frank was a champion of Lack’s view that populations are most often held in check by density-dependent biotic factors. He was a speaker at the famous symposium at Cold Spring Harbor in 1957, which attracted leading ecologists from all over the world (e.g., H.G. Andrewartha, L. C. Birch, G. E. Hutchinson, and A. J. Nicholson) to weigh the relative importance of density-dependent and density-independent factors in limiting populations.

Frank’s breadth of interests in systematics and evolution,

in behavioral ecology, and in population and community ecology stemmed from

his love of natural history and making first-hand observations in the field.

He listened attentively to reports of new discoveries and immediately began

musing about their significance for the grand scheme of evolutionary and

ecological theory. His conversation and writing reflected his broad views,

sometimes with considerable elaboration as he made eclectic references to

relevant information, and always helped provide a more synthetic approach

to the problem. It came as no surprise that after his retirement in 1985

he continued to contribute to the intellectual life of the Museum of Vertebrate

Zoology and the Department of Integrative Biology. He was a regular attendee

at the weekly meetings of the Behavioral Ecology Seminar, and the Museum

Lunch. Ecolunch, which he founded in the 1960s, became a model for informal

lunchtime meetings, a tradition that his former students spread throughout

North America. In addition, he was often consulted for his historical perspective

on the rise of ecology and evolutionary studies in the 20th century.

Frank’s legacy to ecology lives on in his many graduate students and

postdocs (listed below). His style of training research students was simple

and highly effective; he continually asked questions that drew out significant

insights. These cross-examinations took place in a variety of settings:

hallway encounters where he stopped students to discuss a recent journal

article or a new bit of data, seminars and brown-bag lunches, where reasoning

was expected to be more polished, and private lunches in one of Frank’s

favorite restaurants, where he reported his candid observations on personal

issues that were holding back the work. Most of Frank’s students developed

a deep fondness for him because he cared about them as individuals, and

his concern for them went far beyond that expected of graduate advisors.

The closeness between Frank and his students was evident at his 70th and

80th birthdays, when many returned to Berkeley and helped him celebrate

with all-day symposia (dubbed Pitelkafests). Frank’s students also

honored him by establishing the Frank A. Pitelka Award for Excellence in

Research, which is awarded by the International Society for Behavioral Ecology.

Frank’s extraordinary breadth of professional interests was also reflected in the variety of his personal interests. A social conversation with Frank likely would range from music (chamber music and opera were his passions), to art (he had an extraordinary collection of objets d’art), cuisine (he was known by sight at the best restaurants in the Bay Area), and gardening (he was an avid gardener, both in his yard and as a supporter of the University of California Botanical Garden in Strawberry Canyon).

Frank taught introductory and advanced ecology courses throughout his career. He also served in a variety of other capacities. For the University of California at Berkeley, he was Curator of Birds in the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (1958–1963), Chairman of Zoology (1963–1966, 1969–1971), and Associate Director of the MVZ in charge of the Hastings Natural History Reservation (1985–1997). In addition, he edited three journals, Ecology/Ecological Monographs, Condor, and Systematic Zoology, and served on advisory panels for the National Science Foundation, the Atomic Energy Commission, the National Academy of Sciences, and the National Commission for UNESCO. Finally, he was the first Director of the Tundra Biome, a large-scale ecosystem research program in the early 1970s, supported by the National Science Foundation as a United States contribution to the International Biological Program.

Frank received many honors during his lifetime, including the Mercer Award and the Eminent Ecologist Award of the Ecological Society of America, and the Brewster Medal of the American Ornithologists’ Union. He was an elected fellow of the Arctic Institute of North America, the American Ornithologists’ Union, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the Animal Behavior Society, and the California Academy of Sciences, as well as an honorary member of the Cooper Ornithological Society. Because of his background, one of his proudest moments occurred in 1997 when he received an honorary doctorate in biological sciences from Masaryk University in Brno in the Czech Republic. In spite of all these honors for his scientific achievements, the one that he may have valued most was the Distinguished Teaching Award that he received from UC Berkeley in 1984. That award reflected the special relationships that he established with his students.

Finally, we would be remiss if we did not try to convey the

ebullient personality that has led to Frank being described as “larger

than life.” Frank was prone to impatience, a trait that made driving

with him an adventure. His imposing physiognomy and conversational style

commanded attention at any gathering. This led some people to conclude that

Frank was egotistical (or even imperious), when actually he was expressing

his natural enthusiasm and playfulness. Frank’s rich voice, hearty

laugh, adept choice of words, and Darwinian enthusiasm for any new bit of

information all contributed to his charm. He was generous with praise and

took as much delight in the accomplishments of others as in his own. We

shall miss him. Fortunately, he has left a legacy that will not soon be

forgotten.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Connors, Harry Greene, Richard T. Holmes, Walter D. Koenig, Ronald L. Mumme, Louis F. Pitelka, and David W. Winkler, who answered our questions about what was going on during the periods when they were working closely with Frank.

Doctoral students and postdoctoral research associates of Frank A . Pitelka*

Ph.D students

Paul H. Baldwin, George O. Batzli, Donald L. Beaver, Jerram L. Brown, Henry E. Childs, Howard L. Cogswell, Thomas W. Custer, R. Glenn Ford, Arnthor Gardarsson, Russell S. Greenberg, Scott A. Hatch, S. B. Haven, Richard T. Holmes, Walter D. Koenig, Larry R. Lawlor, Stephen F. MacLean, William J. Maher, Michael P. Marsh, David A. Mullen, Ronald L. Mumme, J. Peterson Myers, Gordon H. Orians, Fernando I. Ortiz-Crespo, Oscar H. Paris, Stephen Pruett-Jones, Donald R. Roberts, Richard B. Root, Gregory M. Ruiz, Thomas B. Smith, Susan H. Thomas, William L. Thompson, J. Van Remsen, Nicolaas A. M. Verbeek, Stephen D. West, Pamela L. Williams, David W. Winkler, Jerry Wolff

Postdoctoral research associates

Tom J. Cade, Guy N. Cameron, Peter G. Connors, Janis L. Dickinson, Susan J. Hannon, Charles J. Krebs, Paul W. Sherman, Jeffrey R. Walters

In addition Frank was an important mentor to many ecologists who were never officially his students. We regret that we cannot include these people because the variety of connections makes it impossible to fairly say who was among them.

*This list was compiled from the names found in Pitelka 1993a (in the bibliography below) and in a newsletter of the International Society for Behavioral Ecology. The newsletter, dated May 1996, may be traced by contacting:

Wendy King

ISBE Archivist

Department de Biologie

Universite de Sherbrooke

Sherbrooke, Quebec

Canada J1K 2R1

Selected bibliography

of the ecological publications of Frank A. Pitelka

This selection was drawn from a total of 129 papers in Frank’s curriculum vitae. The list, which is in chronological order, was selected to illustrate how Frank’s interests evolved and to record the breadth of his contributions.

Pitelka, F. A. 1950. Geographic variation

and the species problem in the shore-bird genus Limnodromus. University

of California Publications in Zoology 50:1–108.

Pitelka, F. A. 1951. Speciation and ecologic

distribution in American jays of the genus Aphelocoma. University

of California Publications in Zoology 50:195–464.

Pitelka, F. A. 1951. Ecologic overlap and

interspecific strife in breeding populations of Anna and Allen hummingbirds.

Ecology 32:641–661.

Pitelka, F. A., P. Tomick, and G. W. Treichel.

1955. Ecological relations of jaegers and owls near Barrow, Alaska. Ecological

Monographs 25:85–117.

Pitelka, F. A. 1958. Some aspects of the population

structure in the short-term cycle of the brown lemming in northern Alaska.

Cold Spring Harbor Symposia XXII:237–251.

Pitelka, F. A. 1959. Numbers, breeding schedule,

and territoriality in pectoral sandpipers of northern Alaska. Condor 61:233–264.

Paris, O. H., and F. A. Pitelka. 1962. Population characteristics of the

terrestrial isopod Armadillidium vulgare in California grasslands.

Ecology 43:229–248.

Pitelka, F. A., and A. Schultz. 1964. The

nutrient-recovery hypothesis for arctic microtine cycles. Pages 55–68

in D. J. Crisp, editor. Grazing in terrestrial and marine environments.

Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, UK.

Batzli, G. O., and F. A. Pitelka. 1970. Influence

of meadow mouse populations on California grassland. Ecology 51:1027–1039.

MacLean, S. F., and F. A. Pitelka. 1971. Seasonal patterns of abundance

of tundra arthropods near Barrow. Arctic 24:19–40.

Pitelka, F. A., R. T. Holmes, and S. F. MacLean,

Jr. 1974. Ecology and evolution of social organization in arctic sandpipers.

American Zoologist 14:185–204.

Custer, T. W., and F. A. Pitelka. 1977. Demographic

features of a Lapland Longspur population near Barrow, Alaska. Auk 94:505–525.

Pitelka, F. A., editor. 1979. Shorebirds in

marine environments. Studies in Avian Biology, Number 2. Cooper Ornithological

Society, Lawrence Kansas, USA.

Koenig, W. D., and F. A. Pitelka. 1979. Relatedness

and inbreeding avoidance: counterploys in the communally nesting acorn woodpecker.

Science 206:1103–1105.

Koenig, W. D., and F. A Pitelka. 1981. Ecological

factors and kin selection in the evolution of cooperative breeding in birds.

Pages 261–280 in R. D. Alexander and D. W. Tinkle, editors. Natural

selection and social behavior: recent research and new theory. Chiron Press,

New York, New York, USA.

Ford, R. G., and F. A. Pitelka. 1984. Resource

limitation in populations of the California vole. Ecology 65:122–136.

Mumme, R. L., W. D. Koenig, and F. A. Pitelka. 1988. Costs and benefits

of joint nesting in the acorn woodpecker. American Naturalist 131:654–677.

Koenig, W. D. , F. A. Pitelka, W. J. Carmen,

R. L. Mumme, and M. T. Stanback. 1992. The evolution of delayed dispersal

in cooperative breeders. Quarterly Review of Biology 67:111–150.

Pitelka, F. A. 1993a. Academic family tree

for Loye and Alden Miller. Condor 95:1065–1067.

Pitelka, F. A., and G. O. Batzli. 1993b. Distribution,

abundance and habitat use by lemmings on the north slope of Alaska. Pages

213–236 in N. C. Stenseth and R. Ims, editors. The biology of lemmings.

The Linnean Society of London, England.

Richard B. Root

Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

Corson Laboratory

Cornell University

Ithaca, NY 14853

George O. Batzli

Shelford Vivarium

606 E. Healey St.

University of Illinois

Champaign, IL 61820

Society

Actions

Society

ActionsHighlights of the 21–22 November 2003 Governing Board Meeting

· Accepted the audit for the year ending 30 June 2003.

· Met with ESA-sponsored AAAS Congressional Fellow Evan Notman.

· Received a status report on the Ecological Visions Project and

provided reactions and recommendations to the Visions Committee for consideration

as they finalize their report.

· Discussed plans for a planning retreat in February 2004.

· Agreed to award the Sustainability Science Award at the Awards

Ceremony held during the ESA Annual Meeting.

· Supported prescreening of applicants for the Buell and Braun awards

prior to the Annual Meeting.

· Adopted a Corporate Grants and Sponsorship Policy.

· Reviewed a petition and proposed bylaws for a Canada Chapter and

voted to recommend approval of the Chapter to the ESA Council in August.

· Adopted public policy priorities for the coming year

· Approved criteria recommended by the Publications Committee for

the review of ESA Editor-in-Chiefs and of the Publications Program.

· Appointed Kiyoko Miyanishi as Program Chair for the Memphis, 2006

Annual Meeting.

· Appointed Catherine Potvin, McGill University, and Christian Messier,

University of Quebec–Montreal, as the local co-hosts for the Montreal,

2005 Annual Meeting.

· Reviewed a planning time line for a themed meeting in Mexico in

late 2005 or early 2006, and suggested the theme “Ecological Consequences

of Trade” for the event.

Minutes of

the ESA Governing Board Meeting

21–22 November 2003

The 21–22 November meeting of the ESA Governing Board was attended by Bill Schlesinger (President), Ann Bartuska (Past President), Jerry Melillo (President-Elect), Jill Baron (Secretary), Jim Clark (Vice President for Science), Norm Christensen (Vice President for Finance), Carol Brewer (Vice President for Education and Human Resources), Sunny Power (Vice President for Public Affairs), Margaret Palmer, Ed Johnson, and Oswaldo Sala (Members-at-Large). Also attending were Katherine McCarter (Executive Director), Elizabeth Biggs (Finance Director), Jason Taylor (Education Director), Clifford Duke (Science Director), Sue Silver (Editor-in-Chief for Frontiers), David Baldwin (Managing Editor), and PAO representative Maggie Smith. The meeting was called to order by President Schlesinger at 7:00 pm on Friday, 21 November 2003, and adjourned at 5:00 pm on Saturday, 22 November 2003.

I.

ROLL CALL

A. The GB unanimously adopted the agenda.

B. The minutes from the August 2003 meeting were approved with two amendments

related to wording of the 2–3 August IID, Ecological Visions Committee.

II. REPORTS

A. Meeting with ESA Auditor

Terri Marrs, an auditor with Gelman, Rosenberg, and Friedman, presented the results of their independent audit of the ESA finances for the fiscal year July 2002–June 2003. She reported a clean opinion and stated that it was a very positive year for ESA. Both she and the Governing Board noted that much of the credit belongs to Finance Director Elizabeth Biggs, who is thorough, careful, and well prepared. The financial report was approved unanimously.

B. Meeting with Congressional Fellow

Dr. Evan Notman, the Congressional Fellow sponsored by ESA for 2003–2004, introduced himself to the GB. He is one of 45 Congressional Fellows sponsored by scientific societies this year, and will be on the staff of the Senate Agriculture Committee, working with Senator Tom Harkin of Iowa. He will be working on issues of farm conservation, specifically pesticide regulations. The GB requested that Notman reflect on his year as a Fellow at the ESA Annual Meeting in Portland.

C. Report of the President

President Schlesinger reported on Capitol Hill activities, including letters about the ruling regarding observance of the Endangered Species Act on military bases, fire policy, revisions to the Endangered Species Act, briefings to Senators on the carbon cycle, and an Inter-American Institute letter to Rita Colwell, Director of the National Science Foundation. President Schlesinger noted that Maggie Smith in the Public Affairs Office deserves credit for much of this work, and the GB thanks her. President Schlesinger also noted that enacting the recommendations of the Visions Committee will be a big agenda item in 2004.

D. Report of the Executive Director and Staff

1) Executive Director McCarter noted that ESA staff have been devoting time to redesigning the web site, building Frontiers subscriptions, the Federation of the Americas, manuscript tracking, and education programs. Membership and subscription numbers look good, and the Savannah annual meeting was successful.

2) Education. President-elect Melillo and Education Director Taylor will go to NSF BIO directorate to promote increased funding for SEEDS students to come to ESA meetings, and generally strengthen the links with NSF.

3) Finance Biggs noted that there are 8116 ESA members.

4) Journals. Frontiers Editor-in-Chief Silver reported that there are 83 days from submission to acceptance for Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, and the journal has a 53% rejection rate. The journal is not yet indexed by ISI or BioSys, but Frontiers is under consideration by both. President-elect Melillo noted that advertising still needs to improve in order to cover more of the costs of producing the journal. Managing Editor Baldwin announced the imminent inauguration of manuscript tracking for ESA journals.

5) Science. Science Director Duke noted the significant help provided by Rhonda Kranz to the Visions Committee and to the Science Program overall in 2003. The Weed Science meeting was a success, and credit is due to Lori Hidinger. Duke is preparing a proposal to develop a common statement across many societies regarding data archiving.

E. Reports from Committees

A written report from the Annual Meeting chairman was submitted.

F. Financial Updates

Vice President for Finances Christensen and Executive Director McCarter reported that ESA had a solid first quarter. In stocks, ESA mutual funds are holding steady, while those in the equities fund are slightly higher than they were in January 2003.

G. Federation of the Americas

1) A motion was made, seconded, and unanimously approved to add $600 to the funds Member-at-Large Sala now has to increase the print run of three Spanish-version Issues in Ecology from 450 to 1000.

2) Discussion regarding the possibility that the 450 ESA overseas members receive a hard copy of Frontiers ended with the suggestion that funding for mailing could be an introductory request to a small foundation interested in building international cooperation. Finance Director Biggs will e-mail GB members with the costs of mailing Frontiers.

3) As a result of a suggestion from the Meeting of the Americas in August, a letter of support for the InterAmerican Institute for Global Change Research was sent to NSF.

4) Member-at-Large Sala reported on meetings ESA has had with potential funding organizations to support the activities of the Federation of the Americas. The Organization of American States (OAS) Sustainability in the Environment sections, USAID, and NSF International Programs are all interested with varying levels of available support. President-elect Melillo suggests ESA meet with DEB, GEO, and International Programs in February to inform a greater funding base at NSD.

5) ESA staff are exploring the possibility of holding a theme meeting in Mexico in 2005–2006.

III. DISCUSSION ITEMS

A. Ecological Visions Committee Update

Member-at-Large and Visions Committee Chair Palmer presented a draft report of the Visions Committee, which the GB reviewed and commented on. Among the questions raised during discussion were whether the Visions Report would lead to a sea-change within ESA, what is and what is not part of the role of ESA in implementing the plan, how should ESA bring in partners (national and international), since the vision is larger than ESA alone? Other professional societies named to include early as partners included AIBS, AGU, ASLO, the Agronomy Society, and education societies.

B. A special meeting of the ESA GB will be held February 20 to begin to revise the ESA strategic plan around the recommendations from the Visions Committee.

C. Trends in ESA Revenues, Expenses, And Subscriptions

There was an anticipated decline in individual member journal subscription trends between 1999 and 2003, but institutional subscriptions remained fairly constant. VP Brewer suggested ESA explore the idea of a State University System pricing (“Tier 4”) for multiple universities that share site licenses and subscriptions. It was also suggested that ESA look again into bundling the journals, since students at universities that do not subscribe to one or more ESA journals (such as Duke University) are not exposed to those journals. A discussion of the PLOS initiative noted that there is lots of opposition to the idea of pay-per-view fees for individual manuscripts. Member-at-Large Sala requested to see the trends of Impact Factors for ESA journals in comparison with other society and for-profit journals over time. Other trends observed were increases in both total income and total expenses, with income slightly higher than expenses. The Board asked to see the trends for the Annual Meeting displayed as net revenue per participant. Funding for the Public Affairs Office has not changed since 1999, while other offices within the Headquarters Office have increased. The GB greatly appreciated the information provided by trend lines, and requested similar summaries once a year.

D. Awards Issues

1) Odum Award. Linda Wallace, Chair of the Odum Award, and Carol Brewer, VP for Education and Human Resources, request more recognition for the recipient of the Odum Award, such as presentation of a lecture and/or paper in Frontiers. The GB responded with the idea that the committee consider additional creative activities, such as sponsoring a symposium or a workshop.

2) Buell/Braun Awards. There is a perennial problem of getting enough people to judge Buell and Braun student paper and poster presentations. The GB recommends a pre-screening process and suggests that Sections and Chapters be involved; Secretary Baron will urge Sections and Chapters to support these awards by volunteering judges. VP Brewer will explore student award guidelines from other societies, such as NABS. The Buell/Braun award committee is urged to change the wording of the announcement for submissions to suggest that participation should present the capstone of a student’s career.

3) Sustainability Award. The GB unanimously agreed that presentation of the new Sustainability Science Award be included in the ESA annual award ceremony.

4) Awards Ceremony. The GB agreed that the awards ceremony in the Opening Plenary Session at the Annual Meeting was effective.

E. Canada Chapter

The Board reviewed a petition by 20 Canadian ecologists as well as draft Chapter by-laws and unanimously approved recommending establishment of a Canada Chapter to the ESA Council in August.

F. Corporate Grants Policy

The Board adopted a Corporate Grants Policy for ESA to guide the solicitation and receipt of corporate grants and sponsorships. GB recommended that corporate prospecti and awards are to be approved by the GB prior to solicitation or receipt, and a time limit will be established for how long a sponsor can use the ESA logo.

G. Public Policy Priorities

The PAO proposes that Forest Fire Management, Air Pollution, Endangered Species Act, Marine Issues, Genetically Modified Organisms, and Invasive Species become the topics of focus for 2004. The first four issues are on the legislative agenda, and the last two have pending position papers. Maggie Smith recognized these issues are not exclusive of others that may arise. GB recommended there should be a list of 8–10 experts identified for each of the issues, and will send names of experts to Smith. GB also recommended that a list of the upcoming year’s PAO activities be prepared yearly and brought to the GB in August before the fall legislative session. The list should be reviewed again each May.

H. Editor-in-Chief/Publications Program Review Criteria

The Publications Committee presented review criteria for Editors-in-Chief and for the entire Publications Program to the GB. The GB approves the broad criteria for evaluations. For all EiC evaluations except Frontiers these are: (1) quality and breadth of editorial board; (2) interaction with editorial board and authors; (3) interaction with society membership; and (4) interaction with Managing Editor. For the entire Publications Program, including Frontiers, the criteria are: (1) scientific quality of journals; (2) service to ESA members; (3) scope and breadth of publications; and (4) efficiency and quality of journal production and publication. Details under these broad criteria need not be spelled out explicitly, but the Governing Board requested that the evaluations presented to them reflect how each criterion was specifically reviewed. Review committees for EiC and the Publications Program should be recommended by the Publication Committee to the Governing Board.

I. Meeting Issues

1) Montreal 2005 symposia. The GB voted unanimously to cap the number of symposia at 24 for the joint meeting of ESA with INTECOL, but to encourage all symposia to reflect the international flavor of the meeting. The GB strongly suggests ESA and INTECOL work as partners to develop themes for the symposia.

2) Program Chairs

a) There was approval of Kiyoko Miyanishi as the Program Chair for the 2006 meeting in Memphis, Tennessee, with Ed Johnson abstaining.

b) Names were suggested as possible Program Chairs for 2007 and 2008 and will be forwarded to the Meetings Committee for consideration. The Board looks forward to the Meetings Committee returning with recommendations.

3) Local Hosts—2005. The GB unanimously approved Christian Messier and Catherine Potvin as local hosts for the 2005 Montreal annual meeting.

4) Mexico Meeting

Discussion centered on possible themes and program chairs for a meeting in Mexico to be held in the winter of 2005. The GB felt that the theme of the meeting should be decided before appointing program chairs, and possible topics (partnerships for the planet, ecological consequences of trade, GMOs, and bioprospecting) were added to the list already developed by the Meetings Committee. Theme possibilities should be cycled back to the Federation of the Americas leaders. The Mexico Chapter should be involved in planning the meeting.

J. Position Paper Updates

The GB wonders if the Invasive Species paper under construction by Lodge et al. could be produced in time for the March 2004 AIBS invasive species theme meeting. VP for Science Clark will ask for a ~ 5-page distillation of the Biodiversity paper, which is currently being considered for publication in Ecological Applications or Ecological Monographs. Secretary Baron will check on guidelines for the role of the Governing Board on position papers.

K. New Business. There was no new business.

Respectfully submitted,

Jill Baron, Secretary

Departments

DepartmentsNote: Dr. Harold Ornes is the editor of Ecology 101. Anyone wishing to contribute articles or reviews to this section should contact him at the Office of the Dean, College of Science, Southern Utah University, Cedar City, UT 84720; (435) 586-7921; fax (435) 865-8550; email: [email protected]

The recruitment of new faculty members is an important function

of any university academic department. Once hired, the new recruit

is often faced with a significant portion of their time devoted to

teaching. Of course, another significant portion of time is devoted

to research, and another significant portion of time is devoted to

service.

I think the following article by Karen Wilson, University of Toronto,

and Stephanie Hampton, University of Washington, will be useful for

both rookie and the veteran professors. Whether you are at a R-1 university

or private undergraduate campus, the emphasis on quality classroom

instruction begins with your first semester and continues through

posttenure review. If you can document that you are effectively using

most of these methods and strategies suggested by Wilson and Hampton,

your students will benefit and the teaching portion of your promotion

and tenure application will be applauded.

Harold Ornes

Ecology Teaching Tips for First-year Professors

The first term of teaching undergraduate and graduate courses as a new faculty member is an especially challenging new duty for those who have no previous teaching experience, but also can be unexpectedly difficult for those who thought they were prepared by graduate teaching assistantships. Teaching assistantships introduce us to many fundamental educational concepts, increase our comfort with teaching, and may have even taught us to prepare a lecture or two, but creating and delivering an entire course—or several different courses in the same semester—is often beyond the training graduate students receive. The tips in this article emerged during the fifth DIALOG Dissertations Initiative for the Advancement of Limnology and Oceanography Symposium <http://aslo.org/phd.html> for new Ph.Ds in Limnology and Oceanography as we shared our experiences in the 1-year sabbatical replacement positions we each took prior to our postdoctoral research positions. We both feel we had excellent training as graduate teaching assistants, but were still somewhat overwhelmed when we faced numerous unanticipated questions and challenges in our first year of faculty-level instruction. In these jobs, all our time and energy was consumed by teaching, and we learned to teach in proverbial trials by fire. We have organized the tips into four categories: (1) getting started with a course, (2) teaching style and resources, (3) methods of teaching other than lectures, and (4) course evaluations. Our primary goal in compiling these hints is to deliver some information that would have greatly reduced the first-term panic we felt, and the amount of time we spent in self-instruction. Additionally, we have included many tips for making the experience more enriching for both you and the students. In the busy life of a new professor, incorporating all of these suggestions into your teaching at once would be overwhelming. Start slowly, and allow your teaching to build over time.

1) Getting Started

· When preparing a new class (or revamping an old one), ask

for syllabi, notes, slides, etc. from your advisor, mentors, and fellow

new professors (or whomever you are replacing while they are on sabbatical).

Don’t worry about using other people’s work; you’ll

find yourself modifying other’s lectures to meet your own specific

needs and character. You can return your colleague’s generosity

by giving your benefactor your version of the notes when you have

finished your class, scanning your advisor’s slide collection

into digital form in return, or passing your notes on to the next

sabbatical replacement in line.

· Get to know lab coordinators, IT personnel, secretaries,

grant coordinators, and housekeeping staff quickly and treat them

well. These people are essential.

· Order your “free” examination copy of textbooks

from the publisher at least 6 months before your class will occur.

You may need a letter from your Department Chair confirming the name

of your course and enrollment, but most publishers will send things

for free, or charge only for shipping. Find the publisher’s web

page for information on how to order. Be aware that once you are in

their database, publisher representatives may e-mail and call you

indefinitely.

· Make a syllabus:

o Put some thought into your syllabus as far in advance as possible

(i.e., not the night before the first class).

o Your first syllabus may closely resemble the syllabus of a senior

colleague, but not necessarily. Take ownership of your course.

o Realize that it is initially very rare to have the order of lectures,

and even content, remain the same over the term. Don’t worry

about changing the order of your syllabus as you go along, but do

give students fair warning. However, it is unfair to increase your

students’ workload as the term progresses or change the dates

of major exams or projects.

o Syllabus should state clearly your course objectives, your expectations

for students, and how you will grade the students. Be very specific

with regard to class policies. See below for some topics to cover

on grading.

o Think through the timing of your assignments, exams, long labs,

and field trips. Ask other professors when students are usually bogged

down in midterm exams, and try to have large assignments due at other

times. If your students commonly take a set of courses together, work

with their other professors to set nonoverlapping exam days.

o Scan the Web for examples of syllabi from other courses to give

you an idea on how others have organized the information.

· Set up a course web page. Course web pages are a great way

to keep in contact with students and quickly disseminate information.

Support staff are generally available to help with setting up course

pages, but even simple, functional web pages can be created using

commonly available programs such as the Composer page in Netscape.

o A course web page can be a place to:

§ Post handouts for students to download before or after class;

this system eliminates an enormous amount of paper waste from students

who miss class. If you have students download their own handouts to

bring to lecture, you must post them several days in advance of the

class.

§ Post take-home exams or homework assignments

§ Post instructions for term projects or research papers, course

expectations, or links to other information.

§ Post your updated syllabus and reading list (very useful for

the first time you teach a course when the order of lectures and assignments

is often in flux).

§ Share articles/readings (in pdf format)—note that because

of copyright restrictions, you may need to limit this part of your

web site to your students only (password-protected).

§ Share data files.

· Before the term begins, familiarize yourself with your institution’s

policies and resources for:

o Accommodation of learning disabilities

o Failing students

o Dishonesty issues (e.g., cheating on exams, plagiarism)

o Student mental or physical health

o Know who to call or where to send students if issues arise (they

will, unfortunately)

2) Teaching

· Preparing lectures. For those of you who came of age in

a big-school environment, realize that lectures aren’t the only

way to teach, and, in many cases, may not be the best or most enjoyable

technique!! See Part 3 for some other ideas.

o Time management is critical

§ Limit the time you spend researching and preparing each lecture

– some can do it in 2 hours per 1 hour lecture, but others (like

us) need 6–8 hours per lecture, at least the first time through.

If you are starting from scratch, you’ll need at least 6 hours

per lecture the first time through (and possibly twice that).

§ If you have a chance to prepare some but not all lectures for

a new course before the term begins, prepare lectures for the first

week or so and do a good job outlining your main points for each lecture

for the rest of the term. Then complete lectures that you can spread

out across many weeks so that for the remaining weeks in the term,

you only have to complete two instead of three new lectures a week.

Having a break one day a week will make your first term bearable.

§ Always have a big-picture general-interest lecture or two in

your back pocket just in case things get crazy and you cannot complete

a scheduled lecture. In a Limnology course, we have used topics with

which we are very familiar, such as eutrophication, food webs, and

biomanipulation as “safety” lectures because they often

fit just as well interspersed throughout the course or at the end.

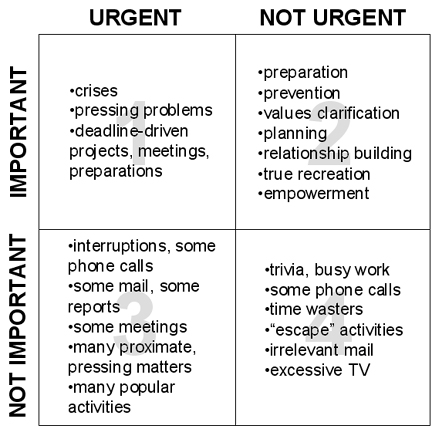

§ See Fig. 1 for suggestions on how to manage your time.

It is helpful to have a copy hanging above your desk.

Fig. 1. At times it helps to be reminded what is really important and urgent, and what is not. Redrawn from Seven Habits Of Highly Effective People by Stephen R. Covey (1990).

o Lecture Style

§ The key point to remember is that students need to be able

to listen to you at the same time that they write notes. Some instructors

try to eliminate note writing by giving extremely thorough handouts

to students, but we have had students tell us that they frequently

stop paying attention if they don’t have to write notes. At the

other extreme, instructors may not provide a handout at all, which

forces students to watch them and write everything. If you use the

latter tactic, honestly evaluate whether your lecture style allows

students to write everything down while listening. We have found that

an intermediate approach, with handouts that function as an outline

of the lecture and include copies of key figures, can be very effective.

§ PowerPoint lectures are a great way to organize information

and present (and archive) photos, figures, and notes in one medium.

· HOWEVER students often dislike PowerPoint lectures because

it is so easy to make them impossible for the student to follow:

o No student can copy notes as quickly as you can flip through slides.

o Students will copy EVERYTHING on your slide, regardless of its relative

importance, and ignore what you are saying while they write.

o If you post your complete PowerPoint lectures on your website, you

may find that students will not attend class.

· Ways to improve PowerPoint presentations:

o Use SIMPLE animation (like “appear”) to bring in one point

at a time when you are actually talking about it (not before).

o Do not use full sentences on your slide; write everything shorthand,

as you’d expect your student’s notes to read.

o Never put a slide up (photo, graphs, or words) that you are not

ready to talk about. If using a photo as a transitional slide, at

least tell the students what it is before launching into a preamble.

This prevents them from wondering, “What is that?” as you

to talk to them.

o Make sure your font is simple (sans serif) and at least 20 pt. For

instance, Arial is easier to read from a distance than Times New Roman.

· Use the board in conjunction with PowerPoint:

o For example, show vocabulary words in PowerPoint, but write the

actual definition on the board.

o For life cycles and other diagrams, work through the details of

life cycles on the board, using simplified, easily copied drawings.

Then use PowerPoint to present a final, full-color version.

o Remember, when you write (or draw) on the board, most students can

keep up with the pace of your writing. This virtually eliminates the

dreaded and disruptive, “Can you go back to the last slide?”

question.

§ Be animated! Enthusiasm is ok! You are on stage!

§ Students love photos. Photos of organisms and places make a

big difference in increasing student enthusiasm. See below for some

tips on resources.

§ Get feedback on your teaching effectiveness as you teach:

· Ask your department chair to watch you teach and give you

feedback. This is especially important if you’ll be applying

for jobs and need a reference for your teaching.

· Some schools offer a service in which specially trained students

sit in on the class and give you feedback on your lecturing. Teaching

assistants can also give you invaluable information on your lecture

style and the corresponding comprehension of your students.

§ Watch your colleagues teach (especially the ones that are well

liked).

o Teaching Tools

§ The best lecture is a good, captivating story, with a clear

message. It is always a good idea to outline exactly what you want

students to get from a lecture in the beginning of your lecture, even

if the lecture is one long story from start to finish.

§ Adobe Acrobat (the program you pay for, not download free)

allows you to copy figures/photographs out of pdf files (i.e., new,

exciting full-color research from Science or Nature). A small golden

key symbol indicates the document is locked and you may not be able

to copy figures (or text), but some files allow you to turn this security

feature off. Be sure to indicate the source for each figure on your

slides as an example of proper citation format and policy.

§ Always keep track of the references you used to construct a

lecture, either at the end of the PowerPoint presentation, or in a

“notes” file. You’ll be happy you did when you revise

or review the lecture later.

§ You can reduce paper waste by saving teaching materials in

electronic format: pdfs of source articles, lecture notes with relevant

references, photos, etc. We suggest archiving your files on a CD after

each term is finished.

o Distill your messages!

§ Beware that it is really, really tempting to dump a huge amount

of information on the students (because you know there is so much

to learn!) but you must resist! Use a message box (Fig. 2)

to figure out your main points and stick with them. Don’t be

afraid to drop a lecture or two and use the time for good discussions

or active learning instead (see below).

Fig. 2. The message box is an excellent method for pinpointing your take-home message in lectures, or in research. Begin by succinctly stating the issue or topic of your lecture. Then consider what the problems are related to this issue, and why students should care. What are the solutions to this issue? How can we benefit from understanding this issue? Be specific and logical. Adapted from materials from SeaWeb.

§ A “question of the day” presented at the end of lecture

is a useful method to challenge students to use what they learned

in lecture that day. You can have them turn in the question the next

lecture for credit (also a way to monitor who is showing up in class)

or use a few of the questions as exam materials. In either case, you

can start the next lecture by bringing up the question and working

with the class to figure out the (an) answer—a good informal

way to start lectures that gets everyone thinking and involved and

provides a bridge between class periods.

o Be approachable!

§ If you don’t know the answer immediately, tell the student

that it’s a great question, but you don’t know at the moment,

and that you would be happy to find out. But ask the student to contact

you for more information, so you don’t have to remember to get

back to that student along with everything else you have to do.

§ Encourage questions in class. Ask colleagues for advice on

soliciting student participation in class; they have a wealth of experience

and a diversity of solutions! For example, you can stage a series

of your own innocuous questions for students just so they can hear

their own voices in class, such as “Has anyone ever seen >insert

interesting phenomenon or organism<?”

§ Set specific times for office hours: students know when they

can definitely find you, and you protect the uninterrupted time necessary

to concentrate on other responsibilities. Requiring students to come

to your office hours in the beginning of the term (to discuss a term

project or receive their first exam) will break the ice and make it

easier for them to return on their own later in the term.

· Information sources:

o Use Google.com/Images to search for photos to use in lectures. It

is not clear what the legality is behind this, but cite the web page

and photographer (if available) and only use the images for educational

purposes. To download the photo, right-click on the photo on the web

page you want, and select “Save as.” Create a digital photo

library classified by subject.

o Build a good personal library of texts, compelling articles, and

your own digital photos for quick reference when making lectures.

The more photos and stories you use, the better the students will

remember your main points. Your school may have personal development

funds you can use for purchasing texts and specialized subject books

that your library may not have. Having multiple textbooks allows you

to judge which to use in class, and you can introduce figures and

examples not used in the students’ text. Other texts provide

a fast way for you to find multiple examples of the same phenomenon

to show your students, when a primary literature search is not possible.

· Creating handouts

o Pass out lecture outlines that follow your PowerPoint lectures.

To easily outline a PowerPoint lecture, put PowerPoint into outline

view, copy the text, and paste into a word-processing program. Paste

into your document as unformatted text or the default. Then copy graphs

and figures directly out of PowerPoint and into the document. In Microsoft

Word, paste PowerPoint figures in as a picture using paste special

(not as a PowerPoint object). Be sure to format the resulting “picture”

as “in front of text” (Go to format/picture/layout/”In

front of text”) so it is easy to reposition the figure.

o Use the handout to outline the lecture, highlight main points, and

provide places for students to fill in extra notes, write out definitions,

and draw on figures. Do not put as much wording on your handout as

you have in your slides. They must WRITE for themselves.

3) Learning situations other than lectures (often much more

enjoyable and memorable for all involved)

· Discussions

o Ways to make discussions successful:

§ A good discussion requires as much preparation as a lecture;

don’t use a discussion when you don’t have time to put a

lecture together.

§ Break your class into small groups (you may want to pre-assign

these groups to speed the process). Mix the groups up from discussion

to discussion.

§ Have the students prepare for the discussion by reading materials

or doing research before class. Insure the preparation is done by

requiring students to turn in a written summary that includes their

opinions on the topic.

§ Use good topics such as current or controversial issues, or

issues to which the students can easily relate. Issues that affect

their family or hometown are often useful. You might also ask the

students to suggest topics.

§ Another form of discussion is to have students take sides,

but again, the more work your do organizing before the discussion,

the better it will go. Do your homework.

§ Be prepared to devote your entire class period to the discussion

if possible. Good discussions take time.

· Student teachers: Another way to give yourself a little

breathing room is to allow students in your course to do some of the

teaching. However, you’ll need to work with the students to make

sure things go well and the class period is worth everyone’s

time, so you should dedicate some time to working with the students